Biography

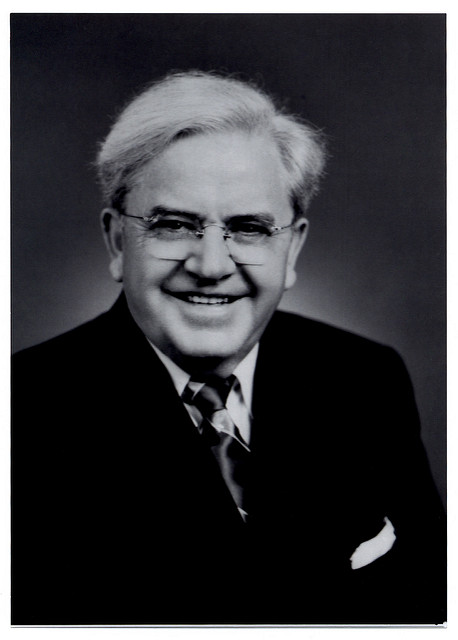

Reuben G. Soderstrom is one of the most dynamic and legendary leaders in the American labor movement, presiding for 40 years—from 1930 to 1970—over 1.3 million members in the Illinois AFL-CIO. A three-volume biography of his life, Forty Gavels, was published in 2017 and takes its name from the annual gift of a handcrafted gavel given to Soderstrom from his membership. He is memorialized in bronze statue in his hometown of Streator, Illinois, in a plaza built by union men and women that includes 12 plaques presenting his most moving speeches.

A successful state legislator, in 1930 the 42-year-old Soderstrom became president of the struggling Illinois State Federation of Labor just as the Great Depression blanketed the nation. He rebuilt the organization through the lean years of the 1930s, rallied behind the policies of the New Deal and then committed his members to a big domestic push to win World War II, including a No-Strike Guarantee during those years.

Following the war, Soderstrom guided his membership in Chicago and downstate Illinois into unprecedented industrial productivity, helped forge the great merger between the national AF of L and CIO, and persistently and presciently pushed for Civil Rights protections at both the state and federal level. Due to his large membership base in a swing state, he was constantly courted by US Presidents and was an important presence in many Washington DC leadership councils.

Early Life

Soderstrom was born on March 10, 1888, on a small farm west of Waverly, Minnesota. He was the second of six children born to John and Anna Soderstrom, Swedish immigrants whose families had journeyed to the United States in search of land, economic opportunity, and religious freedom. His father, John, a Lutheran preacher and cobbler by trade, dreamed of becoming a farmer. In 1886, he leveraged the family’s assets to purchase land, seed and equipment. His efforts were a failure and within ten years the Soderstrom family was mired in debt.

Desperate, John sent his nine-year-old son Reuben to work for a blacksmith in neighboring Cokato, Minnesota, to pay his arrears. Then, in 1900, 13 year-old Reuben traveled alone to Streator, Illinois, in search of better wages. He labored on the trolley lines and in the glass factories, where he participated in his first strike. He eventually saved enough money to move his family to Streator in 1902.

At age 16, Reuben took a job as a “printer’s devil” at the Streator Independent Times. There he came under the tutelage of John E. Williams, a columnist and labor leader who introduced Reuben to the works of many organized labor theorists, economists, and activists including John Mitchell, Richard Ely, and William U’Ren. Soderstrom pursued a career as a union linotypist, apprenticing throughout the Midwest and receiving his union card in St. Louis, Missouri. Soderstrom returned to Streator in 1909, working as a linotypist at the local Anderson Print Shop. After a brief stint in Chicago, Reuben made Streator his permanent home, putting down roots and marrying his longtime sweetheart Jeanne Shaw on December 2, 1912.

Political Career

Reuben joined Streator ITU Local 328 and soon became a fixture in the city’s labor movement. In 1910, he was elected to his Local’s Executive Committee, and was nominated as a delegate to the city’s Trades and Labor Council. In 1912, he was elected President of both his Local and the Streator Trades and Labor Council. After retiring from the Presidency in 1920 he become the Labor Council’s Reading Clerk, a position he held until 1936.

In 1914, Soderstrom made his first run for public office, campaigning for State Representative as a member of President Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party. Although ultimately unsuccessful, the race introduced Reuben to the state political scene. Four years later he ran a successful campaign for State Representative as a member of the Republican Party. After a 1920 loss (largely attributed to his opposition to prohibition) Soderstrom reclaimed the office in 1922 and held it without interruption for 14 years. During that time he earned a reputation as organized labor’s strongest advocate in the Illinois House, authoring and shepherding a series of pro-labor bills through the legislature, including the Injunction Limitation Act, the One Day Rest in Seven Act, the Old Age Pension Act, and anti-“yellow dog” contract bills, as well as increases to education funding and favorable amendments to the workmen’s compensation, occupational disease, and pension laws.

In 1936, Soderstrom lost his statehouse election when he crossed party lines and publicly endorsed Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt for a second term. But his experience in the Illinois House yielded distinct advantages as he advanced his legislative agenda from the outside. Not only were many of those serving in the General Assembly his friends and colleagues, but his status as a former representative gave him the right to lobby legislators directly on the House floor.

Presidency

In 1930, the Illinois State Federation of Labor (ISFL) faced a crisis when its largest union, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), broke apart. ISFL President John Walker, himself a UMWA member, was forced to resign after he and his Progressive Miners of America (PMA) withdrew from the UMWA and claimed to be the “legitimate” miners’ union. ISFL membership dropped to an historic low of fewer than 200,000 members. Leaderless and fractured, the remaining ISFL leaders turned to Soderstrom, a legislator who had recently made a name for himself among laborers for his successful passage of the Injunction Limitation Act. The Executive Committee named him interim President, hoping his political acumen could help save the organization from collapse.

Reuben quickly went to work. Despite his friendship with Walker (and personal distaste for Walker’s UMWA rival John L. Lewis), Reuben took a firm stand against the PMA, refusing to seat them at the 1930 ISFL Convention. The move marginalized the PMA and helped stabilize the UMWA at a critical moment. Just as the miners’ crisis began to abate, however, another, larger threat emerged: The Great Depression.

Over the next decade, Soderstrom guided organized labor through the largest crisis it had ever faced: sustained, pervasive unemployment. By 1933, one out of every four laborers was idle. Reuben combatted the crisis with a mix of legislation, agitation, and recruitment. He fought for relief legislation, including unemployment insurance and a shorter work week. He strengthened union efforts on the ground, traveling across Illinois to give support to strikes and organizing efforts. He also ran a relentless recruitment campaign, focusing not only on unorganized workers, but on established unions not previously affiliated with the ISFL. As a result, Soderstrom saw his membership surge despite the Great Depression and the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO), a rival organization to Reuben’s American Federation of Labor (AFL).

During World War II, Soderstrom took the lead in helping to organize the home front. Illinois became a seat of the nation’s wartime manufacturing, producing more than 246,845 planes, 75,000 tanks, 56,696 Navy vessels, 15,454,714 firearms, and over 37,000,000,000 rounds of ammunition. Reuben helped oversee these efforts as a member of the War Production Board, the War Manpower Commission, and Illinois State Planning Commission. Though invested in victory, he never stopped advocating for workers’ rights, especially worker safety. He pushed back hard against overwork, both in the legislature and as a member of the Illinois Health and Safety Committee and the Advisory Committee for Industrial Safety. He raised money for the war, promoting War Bonds and serving on the Federal War Savings Committee. Near the war's end, he helped shape post-war planning efforts as a member of the AFL’s Peace and Postwar Problems Committee.

Soderstrom’s influence continued to expand in the post-war era. As a direct result of his efforts, Illinois was one of the only states not to be consumed by the wave of anti-labor legislation that shook the country in the late 1940s. He gained the personal confidence of national AFL President William Green, who repeatedly dispatched Reuben as his personal representative to resolve internal disputes across the country and represent the AFL abroad. When George Meany, Green’s successor, began talks with his CIO counterpart to merge the two labor organizations, Soderstrom was one of the handful of leaders—and the only state president—selected to help craft the agreement (specifically with respect to state-level mergers). When his own Illinois State Federation was merged with its CIO counterpart in 1958, Reuben was chosen as the first President of the new Illinois AFL-CIO.

In the Civil Rights era, Reuben worked to bring equality into the workplace. He supported the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) Act, putting the full weight of his organization behind the legislative effort to end discrimination. He was a strong supporter of Jewish efforts to organize both at home and in the nascent nation of Israel, for which he has honored by the Jewish Labor Committee. When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., led a Rally for Civil Rights in Chicago in 1964, Reuben served as an Honorary Chairman, welcoming him to Illinois. Many Civil Rights leaders spoke before the Illinois AFL-CIO at Reuben’s request, including Dr. King and his successor, the Rev. Dr. Ralph Abernathy.

On September 12, 1970, Reuben was named President Emeritus of the Illinois AFL-CIO. He died three months later on December 15, 1970.

Family

Soderstrom was the primary provider for his family since childhood, and continued to care for his mother until her passing in 1959. He was close to his siblings, especially his sister Olga and brothers Paul and Lafe (whose own career in labor politics was cut short when he was killed by a drunk driver in Chicago in 1940).

He was committed to community, and chose to live his entire adult life in Streator and commute to Chicago and Springfield rather than leave his adopted hometown. It was there that he had two children with his wife Jeanne—a son, Carl, and a daughter, Rose Jeanne. Reuben’s son Carl followed in his father’s footsteps, winning the Illinois House seat his father had held in 1950. For twenty years, father and son worked hand-in-hand to introduce and pass pro-labor legislation in Illinois. His daughter Jeanne was a teacher and counselor at Streator High School.

In 1941, Reuben’s son Carl Soderstrom married Streator native Virginia Merriner. Soon thereafter, Reuben became a grandfather for the first time with the birth of Carl Jr. His birth was followed by Virginia Jeanne, Robert, Jane, and William Reuben. Carl Jr. is the founder of the Reuben G. Soderstrom Foundation, and published and co-wrote the biography of Reuben Soderstrom Forty Gavels.